Imagine living in your native country and watching your culture be represented in a way that wholly and completely offends you.

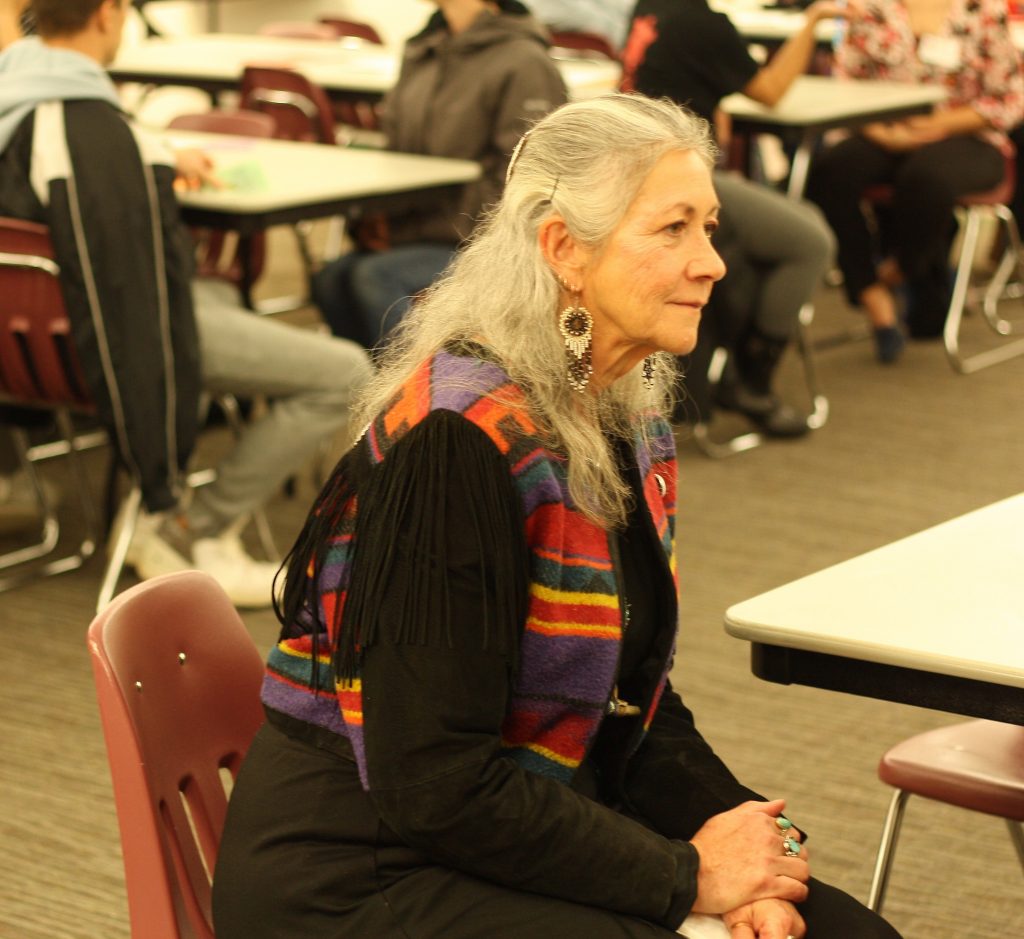

This isn’t a made-up scenario. It has been everyday life for Native American Nancy Simon-Fuchs. Adopted at age three, Simon-Fuchs grew up in the small farming community of Edmore.

“I also taught elementary school for 25 years in White Cloud and our school mascot was the White Cloud Indians,” Simon-Fuchs said. “It was very difficult to be native and to teach in a place where people would say ‘we’re honoring you’ with the most ridiculous costumes and sayings and war-whoops and war chops and stupid caricatures. It’s not honoring, it’s another way of keeping you down.”

Simon-Fuchs said she didn’t begin learning native traditions until after she graduated from high school but since then found her life through them.

“Growing up in the Catholic church, I always felt like ‘what’s wrong with me?’ I would see the old ladies that sit in the front of the pews, tears would run down their faces because they were so full of faith. I never felt that way in church,” Simon-Fuchs said. “But when I was outside, that was church. So this way—these traditions—this has given me life.”

Even more than that, Simon-Fuchs credited her faith and traditions with helping her survive one of the most trying times in her life when her son died at the age of 21.

“I can talk about Josh without crying now,” Simon-Fuchs said. “Now I can cook for him, his favorite foods and I can talk to him and say, ‘you know, I’m making this just for you, kiddo’ without crying. The Catholic church could have never done that for me. So it’s that faith and belief for me that clicked. If I had not found a way to connect with that faith, I don’t know if I could have made it.”

Though she started practicing her traditions after the Religious Freedom Act was passed in 1976, Simon-Fuchs said she saw the oppression in others before it was passed.

“I do know people who were taken away from their families, who went to the boarding schools. They’re still alive, they’re not dead; they’re in their 60s and 70s and trying to deal with a childhood that was ripped away from them,” Simon-Fuchs said. “It is hard to believe that all of this had to be hidden, people had to hide and have ceremonies at night. They were beaten for speaking their language.”

The Ojibwe language was never a written language, which made it hard to pass down. The only way to keep the language alive was through verbal songs and stories.

“You could only learn things by going to ceremonies and singing the songs over and over again,” Simon-Fuchs said. “Just imagine losing the words because they were beaten out of you. You might remember the tune but not the words.”

Click here for a recap of Ferris’ Circle of Tribal Nations’ Ghost Supper event.