In 2023, various states introduced over 110 bills that aimed to restrict the teaching of topics including race, gender and American history in both primary and secondary education.

These bills are annually cataloged and defined as “gag order bills” by the nonprofit organization PEN America.

While the most notable legislation tends to emerge from the American south, such as those colloquially known as “Don’t Say Gay” and Stop WOKE from Florida, the culture surrounding history education can be felt as far north as Big Rapids.

Eye on Ferris

History professor Dr. Tracy Busch first began teaching at Ferris 17 years ago with a doctorate in Russian and European history. She speaks in on-campus Passion for the Past presentations about the war in Ukraine alongside her husband, a former United States Marine who has gone on multiple self-funded missions to Ukraine.

“I think the reason history has been oppressed, and [people] try control it, is because it’s so powerful,” Busch said. “It is just a powerful discipline, because there’s so much evidence that you can produce.”

Another area of Busch’s passion is Ferris’ Museum of Sexist Objects. After being featured in a 9&10 News Segment, the MoSO attracted the attention of conservative news outlet The College Fix.

The College Fix was founded by Detroit native and Hillsdale College’s journalism director John J. Miller. They aim to train young journalists who will “commit themselves to the principles of a free society.”

Busch experienced no hostility from the outlet herself. However, the article titled “Activist professor, DEI officer build ‘sexist objects’ campus collection inspired by racism museum” garnered some negative comments.

One interaction posted on The College Fix’s website reads as follows:

“Whew, it is hard to wade through fresh bull manure.”

“Made harder by how deep the manure seems to run in our educational sectors.”

Dean of the College of Arts, Sciences and Education, Dr. Randy Cagle, sees higher education as a “lightning rod.” When students are taught to think critically, that practice often manifests itself in questioning authority.

“What we’re starting to see is that there are attempts by organizations on the political right to fix what they regard as a kind of a left-leaning or liberal, progressive bias in higher-ed,” Cagle said. “It’s invariably humanities and social sciences programs that sort of get charged and questioned.”

This was not the first time a member of Ferris’ history program drew mass attention and criticism. One position has been left vacant for nearly two years following a viral video and court settlement.

In a segment he called “More Bad News,” Dr. Barry Mehler encouraged students not to attend his in-person classes during the COVID-19 pandemic. The professor presented the information in the video in character, using profane language and dramatic metaphors.

Mehler’s reference to students as “vectors of disease” reached the New York Times.

Mehler, longtime history professor and founder of the Institute for the Study of Academic Racism, was first suspended by the university in January 2022. He settled for $95,000 and retired in July 2022.

Before signing a three-year gag order prohibiting the professor and the university from publicly criticizing each other, Mehler said his right to free speech was violated as Ferris conducted an investigation of his actions.

Without Mehler, the history program now stands with three tenured or tenure-track professors and one who has worked as an adjunct for six years.

The university’s role

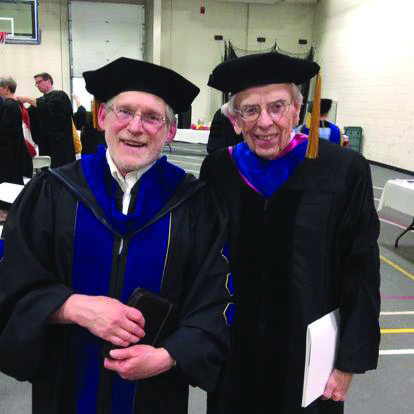

Professors Dr. Gary Huey and Dr. Jana Pisani both moved from southern states to work closer to family in Big Rapids. They have

taught in the history program for 37 and 21 years, respectively.

History classes are typically not required for students outside the history program. Still, faculty believe that the skills offered in a history classroom will be relevant in any occupation.

“Soft skills are life skills,” Pisani said.

These skills include research, collaboration, constructing arguments and understanding the world’s diversity.

When Ferris introduced a bachelor’s degree in history two decades ago, Huey believed things were “looking up” for the program. Today, neither professor expects to see an increase in tenured faculty members in the near future.

Huey sees the university as “enrollment driven,” which may overlook the student credit hours that history courses bring in. Dean Cagle, however, remains hopeful. He does not see any program at a “disadvantage” for gaining tenured faculty simply because they work in the humanities department.

“It’s my job then to get with the history department and envision where we might go next,” Cagle said. “They’re all very innovative thinkers. It’s a discussion that really has to happen between the history faculty, the humanities faculty, me and the provost in coordination with academic affairs as a whole. I’m very optimistic about the history department.”

Huey believes that proper university support for the program is visible inside and outside of the classroom. This could come in the form of funding for new technology and conferences, or the infrastructure to arrange interdisciplinary history courses.

This desire for more support from the university is shared among Ferris’ own history scholars.

Next generations

Senior Brent Baumunk calls himself a non-traditional student. He spent 20 years as a blue-collar warehouse worker before studying history. He is now the president of Ferris’ Phi Alpha Theta history honor society and works with Dr. Busch in the MoSO.

“It would be nice to see Ferris put more effort into its humanities program instead of trying to erase it, which is what it seems like it’s doing. I think it’s a crying shame,” Baumunk said.

Baumunk has hope that the attitude may change under President Bill Pink’s administration. Until then, Baumunk feels that his program is less prioritized than others. He believes that Ferris is and should remain more than a “tech-school.”

“For such a small school, we’re incredibly lucky to have the history program that we do, and I really wish the university would acknowledge that,” Baumunk said. “All four of these professors are incredibly dedicated and wonderful people that could probably get paid a hell of a lot more if they went somewhere else. But instead, they choose to come and stay here.”

As the efforts to restrict history education continue to roll out across the country, Baumunk commends Ferris’ faculty for calling those attempts what they are.

“The only thing you can do is speak out about it,” Baumunk said. “You have to point out that what you’re doing is erasing history. What you’re doing is wrong. What you’re doing is a form of propaganda. It’s shaping the narrative. At Ferris, we have four extremely wonderful history professors that do just that,” Baumunk said.

It’s hard to discuss historical revision and propaganda in the 2020s without mentioning Russia. Ferris alum Richard Byington lived in Arkhangelsk for three and a half years to earn his master’s degree from the Northern (Arctic) Federal Russian University.

After studying in the U.S. and Russia, Byington believes that both countries have had a “similar problem” of misconstruing historical events to fit a certain narrative. He compared Russia’s historical justification for the war in Ukraine to American politicians’ efforts to restrict information taught in critical race theory.

“Those kinds of things are really dangerous because the data is there, the history is there, what happened is there.” Byington said. “When you can look at things and say that this is categorically untrue, or unsound logically, that’s when you start having problems. Unfortunately, some governments are in control of that information.”

Ferris’ history courses sent Byington on an educational journey that has stretched across hemispheres. To him, it doesn’t matter where you’re educated, but what you do with your education.

It’s impossible to predict the future of history, whether it be on campus or across the nation. The story will continue as long as there are dedicated instructors to teach it and eager students to learn it.