Article by: Keith Salowich and Marley Tucker

The potential environmental impacts of Nestlé increasingly pumping groundwater in Osceola County concerns residents as controversy over the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) permit continues.

Nestlé is currently allowed to pump 250 gallons of groundwater per minute. They’ve applied for a permit to increase that to 400 gallons per minute or 210 million gallons a year.

Nestlé doesn’t expect any adverse impacts on the environment and are waiting for DEQ approval.

“I have been the aquatic biologist that’s in charge of evaluating the streams and waterways in the vicinity of areas where they’re operating,” said Ferris adjunct biology professor Doug Workman. “I link my data with a team of experts. They have all kinds of experts and we all collectively exchange our information to evaluate the system for Nestlé.”

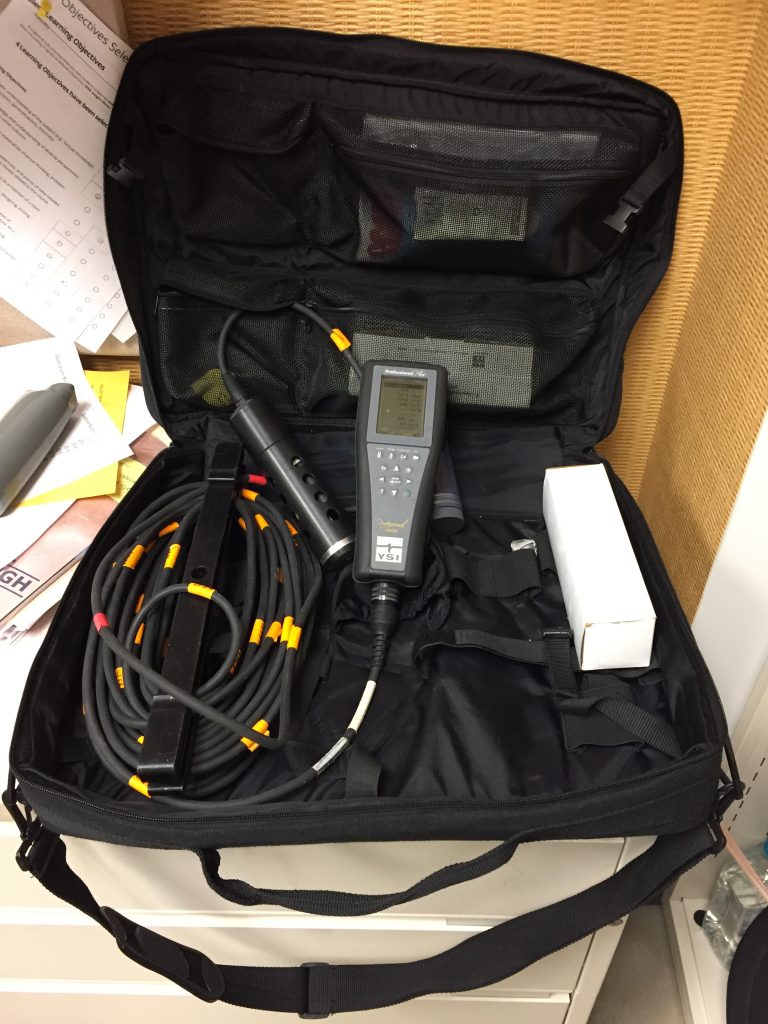

Workman, who has been commisioned as a consultant for the company since 2003, surveys the fish and macroinvertebrate populations and basic water quality of seven different sites near Nestlé’s bottling plant in Stanwood.

“[American brook lamprey are actually pretty sensitive to changes in water quality through sedimentation. The fact that we have things like brook trout, brown trout and these lampreys are important indicators that this is a fairly high quality system,” Workman said.

To gather data on fish populations, Workman uses a backpack electroshocker to discharge electricity into the streams which temporarily stun the fish, then collects them, identifies and measures them and releases them unharmed back into the stream. “Indicator species,” such as the American brook lamprey, are sensitive to environmental changes and therefore can provide information on whether there’s been, “some type of degradation in the environment,” Workman said.

According to Workman, his data has also shown that composition and abundance of macroinvertebrates in the streams near Nestlé’s plant have remained consistent since 2003, as has the water quality and relaitve size of the streams.

“The streams still look, and from the measurements we collect, appear to be the same streams that they were prior. There is some water that’s no longer there because it’s being pumped out,” Workman said.

In 2005, the Michigan Citizens for Water Conservation (MCWC) won protection of a stream system deprived of 24 percent of its water as the result of Nestlé’s pumping and diversion of water for the sale of bottled water.

“I actually made the choice to read the entire report submitted to the DEQ. It’s like a 50-page application and it talks about all the things that could be impacted,” said Ferris biology professor Scott Herron. “They’re saying it will have local drawdown meaning it will draw down the local creeks that eventually connect to the Muskegon River. The environmental impacts become questionable. It may be minimal if you’re only drawing down a creek a couple of centimeters or inches. If you don’t have dry years it might not be a big deal. If you do have dry years it could be a bigger deal. That’s a small flow of what is the Muskegon River.”

In a letter penned Jan. 17, DEQ director Heidi Grether wrote that the agency will consider the entanglement between tie-barred state laws that regulate withdrawal of more than 200,000 gallons of water per day for bottling when reviewing Nestlé’s application to increasing groundwater withdrawal in Osceola County.

Osceola County is nearly 37 minutes from Big Rapids.

The groundwater Nestlé wants to collect would be bottled at two new bottling lines at the company’s plant in Stanwood in Mecosta County, which would add 20 new jobs to the facility.

Some are concerned with the justification of adding jobs to the local economy by overlooking potential environmental harms such as the plastic used in bottling the water. According to research and consulting firm Beverage Marketing Corp., bottled water surpassed carbonated soft drinks to become the largest beverage category by volume in the United States in 2016.

“How many millions of gallons are we talking about? How many plastic water bottles and what’s happening with those water bottles,” Herron said. “Am I going to see those things in my local environment? Those are unaccounted for issues that need to be considered, too.”

Concerns about oversight are also the focus of those opposed to Nestlé’s request.

Currently, Nestlé monitors and collects the data for the White Pine Springs Well 101, located in Osceola Township, through a contractor. MCWC are seeking that all future monitoring and data collection associated with all Nestlé water taking permits be monitored by the U.S. Geological Survey.

CWC also wants Michigan Governor Rick Snyder to impose a two-year moratorium on water withdrawal increases and new permits. Ontario, Canada, did something similar beginning in 2017 to fix their water laws and procedures.

The state will be holding a public hearing on the matter 7 p.m. Wednesday, April 12, which will be preceded by an information session at 4 p.m. on the same day. The event will take place in Ferris’ University Center, and those wishing to speak during the public hearing must sign up ahead of time at the information session.