By: Keith Salowich & Marley Tucker | Editor in Chief & Torch Reporter

Nestlé has landed in hot water as Michigan citizens push back against their effort to increase the amount of groundwater the bottling company takes from the state.

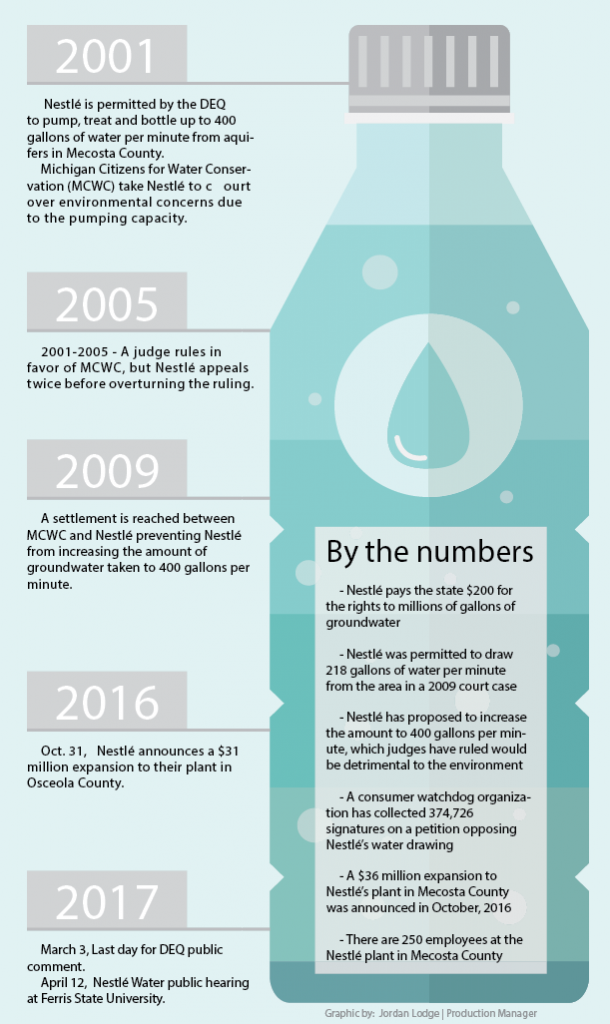

Nestlé Waters North America, the world’s largest bottled water company, has many ties in Michigan as the company has extracted billions of gallons of groundwater from aquifers in multiple locations within the state since May 2002.

Michigan, a state known for its freshwater lakes, charges water bottler companies such as Nestlé $200 per year to operate. There is no state tax, licensing fee or royalty connected with the company’s extraction of groundwater.

“So they’re not paying for the water, they’re not paying much if anything for the taxes and then they’re charging more per gallon of water if you go with bottles than gasoline or milk,” said Ferris biology professor Scott Herron. “The state is not really benefitting from it and the local economy is minimally benefitting.”

Nestlé announced a $36-million expansion at its bottling plant in Stanwood. This expansion would add 20 new jobs to the plant that employs 250 people.

Many residents have been upset after it was revealed that the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) wanted to approve a 167 percent—from 150 gallons per minute to 400 gallons per minute—increase on a well Nestlé owns in Osceola County. That means that they would be pumping nearly 210 million gallons of groundwater per year for $200.

“It kind of made me upset about it because I heard that it was going to impact the watershed down here in Big Rapids,” said Ferris business administration junior Rachael Milkey. “One of my favorite things to do, especially when the weather is nice, is to go hike along the (Muskegon) River, and I’ve already noticed that it’s been down lately.”

Issues with Nestlé aren’t unprecedented. Michigan Citizens for Water Conservation sued Nestlé in 2001 due to the potential environmental damage that its groundwater withdrawals would cause.

“They were asking, ‘would their withdrawal of water negatively impact the local environment, the local aquifer, the local water.’ The evidence that was produced caused the judge to say, ‘It appears that there would be an environmental harm at the required or requested rate of 400 gallons per minute,’” Herron said.

A settlement agreement was reached in 2009, restricting Nestlé’s maximum extraction to 218 gallons per minute in a Mecosta County drawing site.

People have also been angry about the lack of transparency from both the DEQ and Nestlé. The public window of review through the DEQ has been pushed back multiple times in wake of negative comments made about the process.

“Allowing companies like Nestlé to do whatever they want undermines the public water system we all rely on and people are taking note,” said Liz McDowell, campaign director at SumOfUs, an international consumer watchdog organization. “The upswell of public interest in stopping Nestlé’s greedy water grab has been overwhelming—the DEQ is currently receiving a flood of public comments opposing the Nestlé proposal.”

A petition created by SumOfUs opposing Nestlé is currently backed by 374,726 signatures, 66,000 of whom are Michigan residents.

Issues surrounding water are especially controversial in the Great Lakes state, due to an ongoing water crisis.

Residents of Flint, just two and a half hours away from Big Rapids, have been without clean water for 1,058 days as of March 18, 2017.

“I think it puts a sour taste in people’s mouths when they see that Nestlé is taking in water for so cheap and people in Flint can’t even get clean water. It definitely changes how people look at it, especially because Flint hits so close to home,” Milkey said.